Equations of Motion¶

In this class, we will not undertake a formal derivation of the fluid equations of motion. That would take up too much time and require too much math. Interested students can consult Marshall and Plumb (sec. XX) for a more in-depth derivation. Instead, we will try to build an intuitive understanding of the equations of motion based on things we already all understand.

Newton’s Second Law for a Water Parcel¶

The starting point for understanding the equations of motion is the notion of a “water parcel”. The water is hypothetical, infinitesimally small fluid element. We imagine the fluid to be composed of an infinite continuum of such parcels, each following its own unique path.

The equation of fluid motion is basically just Newton’s second law applied to this parcel. Newton’s second law states that

where \(\mathbf{F}\) represents the sum of all forces acting on the parcel, \(m\) is the parcel mass and \(\mathbf{a}\) is the acceleration of the parcel. Both sides of the equations have the units of N (Newtons; 1 N = 1 kg m s\(^{-2}\)).

The expression above is valid for a finite-sized object, like a cannon ball. To move to an infintessimally small water parcel, we replace \(m\), the mass, with \(\rho\), the density, i.e.~the mass per unit volume:

The force vector \(\mathbf{f}\) now represents the force per unit volume and has units N m\(^{-3}\).

In order to develop this equation into a useful form, we need to work on the following two problems:

What is the acceleration of a fluid parcel on a rotating, spherical planet?

What are the different forces that make up \(\mathbf{f}\)?

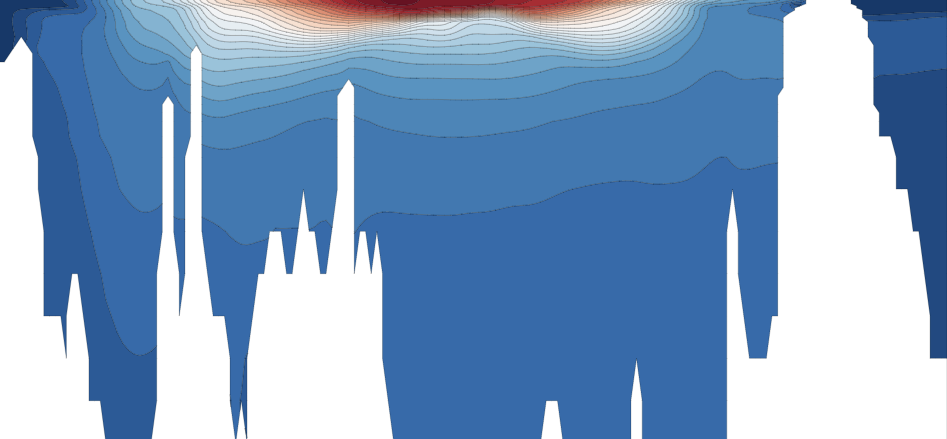

Cartoon of a water parcel moving through space along a path (black line). The colored arrows represent the different forces on and acceleration of the parcel.

We will start with the forces, because they are easier. There are three forces we have to consider: the pressure gradient force (\(\mathbf{f}_p\)), the gravitational force (\(\mathbf{f}_g\)) and the viscous force (\(\mathbf{f}_{visc}\)). Together these sum to give the net force:

Forces¶

Pressure Gradient Force¶

We all have an intuitive understanding of pressure. Pressure is the force the surrounding fluid exerts perpendicular to the water parcel surface. We denote pressure with the variable \(p\): it has units of Pa (Pascals; 1 Pa = 1 N m\(^{-2}\)). Pressure is isotropic, i.e. it is the same in all directions.

If the pressure field is uniform, there will be no net force exerted on the water parcel, because the force is exactly the same on all sides. Only if there is a pressure gradient does the parcel feel a force; the parcel is pushed away from the higher pressure towards the lower pressure. Mathematically, this becomes

Gravitational Force¶

The gravitational force per unit volume on the fluid parcel is given by

where \(g \simeq\) 9.8 m s\(^{-2}\) is the gravitational acceleration and \(\hat{\mathbf{k}}\) is the unit vector pointing “up”, i.e. away from Earth’s center of mass. A slightly more general form is to express this force in terms of the gravitational geopotential field \(\Phi_g\) of earth:

The gravitational vector \(g \hat{\mathbf{k}}\) is defined as the gradient of \(\Phi_g\).

The gravitational force acts to pull all fluid parcels “down” towards the Earth’s center of mass. However, because of the factor of \(\rho\), it is less strong for less dense water. What matters is the relative difference of \(\mathbf{f}_g\) between different fluid parcels. This leads to the concept of buoyancy (discussed in more detail below), which can push water parcels both downward and upward.

Viscous Force¶

Viscosity represents the molecular friction that occurs within the fluid as is moves. The viscous force is given by the formula

where \(\mathbf{u}\) is the fluid velocity and \(\mu\) is the dynamic viscosity, a molecular property of the fluid. A representiative value of \(\mu\) is 1.3 \(\times 10^{-3}\) N s m\(^{-2}\).

It can be easier to understand the viscous force if we consider flow in only one direction. Consider a zonal flow \(u(y)\) that varies in the y-dimension, as shown in the cartoon below. In this case, the viscous vorce in the x-direction is given by

Which is proportional to the curvature of the profile \(u(y)\). The cartoon illustrates a typical jet, with enhanced velocity at the jet axis. The curvature of such a jet profile ensures that the viscous force is negatuve, such that it acts to retard the jet, with a maximum magnitude right at the jet core. One interpretation of this situation is that viscosity diffuses momentum away from the jet core towards the jet flanks.

Viscosity is mathematically and physically analagous to diffusion.

Acceleration¶

Defining position, velocity and acceleration¶

A water parcel’s position at a given time \(t\) is given by a three dimensional vector \(\mathbf{x}(x,y,z,t)\). The instantaneous rate of change of the position of such a fluid element defines the fluid velocity:

The rate of change of velocity is acceleration:

If we planned to use the Lagrangian approach for describing the fluid motion (following each water parcel around), we could leave it at that. But we intend to use the Eulerian approach (measuring quantities at fixed locations in space). We need to recall the definition of the material derivative from the advection / diffusion lecture. The rate of change of any water parcel property in the Eulerian frame is given by the material derivative

Applying this to acceleration gives

Rotating Reference Frame¶

Newton’s second law only applies with an inertial frame of reference. Yet we make our observations of the ocean from on the rotating Earth, most definitely a non-inertial reference frame. This complicates matters significantly. In order to relate the velocity and acceleration we actually measure to the velocity in the inertial reference frame, we need to understand how to transform vectors from a rotating to a non-rotating reference frame.

Dennis Nilsson CC BY 3.0 license, via Wikimedia Commons

The rotating reference frame rotates at rotation rate \(\mathbf{\Omega}\) relative to the inertial frame. \(\mathbf{\Omega}\) is a vector which points along the axis of rotation, following the right-hand rule. The magnitude \(|\mathbf{\Omega}|\), measured in radians / s, gives the rotation rate. For Earth \(|\mathbf{\Omega}| \simeq 7.29 \times 10^{-5}\) s\(^{-1}\).

Let \(\mathbf{v}\) denote an arbirary vector and \(( d \mathbf{v} / dt )_R\) its rate of change measured in the rotating reference frame. The rate of change of this vector in the inertial reference frame is given by

The second term on the RHS, the cross product between \(\mathbf{\Omega}\) and \(\mathbf{v}\), is due to the motion of the rotating reference frame relative to the inertial reference frame.

We now apply this rule to velocity and acceleration. Our goal is to arrive an an expression for the acceleration in the inertial frame, but we start with the velocity. The velocity in the inertial frame is given by

The acceleration in the inertial frame is given by the rate of change of velocity in the inertial frame:

The derivation above shows that, when measuring acceleration in the rotating frame, we need to add two additional terms (both proportional to \(\mathbf{\Omega}\)) in order to recover the acceleration in the inertial frame (which is what we need for Newton’s second law).

Centrifugal Acceleration / Force¶

The term \(\mathbf{\Omega} \times \mathbf{\Omega} \times \mathbf{x}\) is called the centrifugal acceleration. It is a function of position only. Specifically, it is a function of the distance from the Earth’s rotation axis \(r\), and it points outward away from the rotation axis:

where \(a\) is the Earth’s radius and \(\varphi\) is latitude. It is common pracise to move the centrifugual acceleration to the right hand side of equation of motion and call it the centrifugal force. It is a “fictious” force that is felt by observers in the rotating reference frame. We define this force as

where

We combine it with the gravitational potential to form a single “effective” geopotential:

Because Earth’s surface naturally conforms to this geopotential, we don’t have to worry about it in practice. We simply treat \(\Phi\) as the gravitational field.

Coriolis Acceleration¶

The term \(2 \mathbf{\Omega} \times \mathbf{u}_R\) is called the Coriolis acceleration (or, on the right hand side of the equation, the Coriolis force). It can be interpreted as another fictious force that is felt in the non-rotating reference frame.

It is instructive to look at the equation of motion including only the acceleration and coriolis terms:

(We have dropped the subscript \(R\); everything is assumed to be measured in the rotating reference frame.) This equation tells us that the fluid will be accelerated in a direction perpendicular to it’s velocity. A fluid parcel that obeys this equation would appear to move in a straight line in the inertial frame, but follows a curved path in the rotating frame. This sort of motion is called an inertial oscillation.

Putting it all together¶

The full equation of motion, in the rotating reference frame, can now be written as

It is common to divide through by \(\rho\) to obtain the form

where \(\nu = \mu / \rho\) is called the kinematic viscosity.

Common Approximations¶

The full equations of motion are hard to solve and, in many cases, unnecessarily comlex for the study of large-scale ocean circulation. Below we review some of the common approximations used to simplify the equations.

Hydrostatic Balance¶

The vertical component of the equation of motion is dominated by the effect of gravity. The dominant balance is between the gravitational force and the pressure gradient for; this is called hydrostatic balance:

where \(g = | \nabla \Phi |\) is the combined gravitational and centrifugal acceleration coefficient.

Boussinesq Approximation¶

We have already seen the Boussinesq approximation, which states that density variations \(\delta \rho\) are very small compared to the background density \(\rho_0\), i.e.

The background density \(\rho_0\) is in hydrostatic balance with a background pressure gradient, such that

What remains of the pressure is called the dynamic pressure \(\phi\); it is usually normalized by \(\rho_0\), for reasons that will become clear:

We now examine what happens when we apply the boussinesq approximation to the equations of motion. The left-hand side becomes

Because \(\rho_0\) is so much greater than \(\delta \rho\), we simply drop the $\delta \rho term to obtain

We will divide the whole equation through by \(\rho_0\) to remove it from the left-hand side. Let’s now consider together the pressure and gravity terms on the right-hand side:

Because of how we defined \(p_{ref}\), it cancels with the gravitational term proportional to \(\rho_0\), leaving just

Using our definition of \(\phi = \delta p / \rho_0\), and defining the buoyancy as

we can rewrite these terms as

As for the viscous term, we simply approximate \(\nu \simeq \mu / \rho_0\), leading to the final form of the Boussinesq equations of motion:

This is the equation we will use for our study of dynamical physical oceanography.

Coordinates and Approximations for the Sphere¶

For describing the global ocean circulation with the highest precision, one should work in spherical polar coordinates (longitude \(\lambda\), latitude \(\varphi\), and radial distace \(r\)). However, this turns out to be unnecessarily complicated for the things we will study in our class.

Instead, we will use a local tangent plane approximation, as illustrated in the figure below.

By Mike1024 [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

In this approximation, we assume we are looking at region small enough that the Earth appears locally flat, such that we can use cartesian geometry. This region is centered around position \(\lambda_{ref}\), \(\varphi_{ref}\). The local cartesian coordinates are then defined as

name |

direction |

velocity |

local coord |

relation to spherical coord |

|---|---|---|---|---|

zonal |

east |

\(u\) |

\(x\) |

\((\lambda - \lambda_{ref}) \cos(\varphi) / a\) |

meridional |

north |

\(v\) |

\(y\) |

\((\varphi - \varphi_{ref}) / a\) |

vertical |

up |

\(w\) |

\(z\) |

\(r - r_{ref} \) |

where \(a\) is the Earth’s radius.

As a further approximation, we only keep the components of the Coriolis force that act in the horizontal plane on the horizontal velocities. This turns out to be a very good approximation, due to the small aspect ratio of the ocean and the relative smallness of the vertical flow.

We can now write the Boussinesq equation of motion in component form:

We have introduced the Coriolis parameter \(f = 2 \Omega \sin(\varphi)\). The coriolis parameter varies from zero at the equator to its maximum value of \(2 \Omega\) at the pole. This reflects the cross product in the full Coriolis acceleration (\(2 \mathbf{\Omega} \times \mathbf{u} \)). At the equator, the horizontal flow occurs in a plane parallel to the rotation vector and thus experiences no effective Coriolis acceleration. At the pole, the horizontal flow is completely perpendicular to the rotation vector.